Between 2012 and 2017, a series of street art1 “campaigns” (s. hamla, pl. hamlat) have transformed public spaces in Yemen through artistic expression used to provoke political awareness and mobilization. Defined as “campaigns,” artistic interventions on the walls of Sana’a have taken place in a collective manner with the objective of identifying subjects of social and political concern. In certain cases, they have provoked changes at the institutional level, having an effect on the population outside of the participants in the campaigns and triggering other forms of participation and expression of political grievances. This use of street art cannot be understood without taking into account the contentious mobilization that gave place to demonstrations, massive and long-standing sit-ins, and the ousting from power of former president Ali Abdallah Saleh in 2011.2 Initiated by a self-proclaimed “youth of the revolution” (shabab al-thawra), the occupation of public space through indefinite sit-ins spread throughout the country, adding new faces to a political opposition previously limited to political parties and human rights organizations among other social actors. Gradually, antigovernmental demonstrators came to modify old repertoires of contention,3 such as the demonstration or the temporary sit-in, into what became a permanent camp and a new space of resistance at the heart of Sana’a, subsequently named Change Square (saha at-taghyir).

The physical and social space of the streets served as the locus of collective expression, echoing the notion of street politics developed by sociologist Asef Bayat (1997). Furthermore, this sit-in became a political arena where people actively participated in transforming the Square into a sort of parallel city, where a more structured and institutionalized site of discursive interaction developed. This arena effectively resonates with the notion of public sphere, elaborated by philosopher and sociologist Jürgen Habermas who studied the emergence, transformation, and disintegration of the bourgeois public sphere through an analysis of coffeehouses in Great Britain and France in 1680 and 1730, respectively. His (Habermas, 1989/2011) study identified these spaces as a sphere between civil society and the state, where informed and critical discourse by the people emerged. Many Middle Eastern countries and the larger Muslim world of many areas have been examined through his analytical approach,4 though not in terms of artistic activity and expression.

Visual artists were also among the shabab al-thawra of a sit-in that lasted through early 2013. Some of these artists exhibited their works inside the Square, photographed life and death in the sit-in, and more generally participated in supporting the popular mobilization. Artistic expression was also noticeable outside the Square, where graffiti and street art techniques such as free writing, mural painting, or stenciling were used throughout 2011 to reproduce political slogans in unauthorized places, aiming to support the overthrow of Saleh’s regime. In various manners, artistic practices contributed to the symbolic aspects of this mobilization both inside and outside of Change Square.

In 2012, as a continuation of street politics developed in places such as Change Square, a small number of visual artists incorporated dissent, transgression, and civil disobedience into their artistic practices. Such is the case of Murad Subay, the painter who initiated the series of campaigns I analyze in this article. Sending an open call through Facebook in March 2012, he started the first of a series of artistic actions that initially aimed to “color the walls” of bullet-marked spaces where violent confrontations took place between pacifist demonstrators and forces loyal to the regime. Encouraged by large public participation and media coverage, he undertook other street art campaigns, where a contentious discourse and the potential to mobilize people became more evident. Being among the youth who initiated the sit-in in Sana’a in 2011, his practice serves to explore the implications of direct political participation as well as civil disobedience learned under the tents and expressed through artistic practices that uses both walls and streets as canvases and exhibition spaces that are public, free, and not always subject to prior and official authorization.

This case study focuses on the intersection of space, contentious politics, and artistic practices, interrogating how dissent is expressed through street art rooted in street politics. More specifically, it questions the conditions that allowed street art to encourage political engagement, mobilize people, and provoke instances of collective action5 in Yemen. In this sense, this case shows that visual expressions located in the streets not only reflect a vivid political public sphere understood as a site of critical debate and interaction. Furthermore, it introduces a series of dynamics that make of these campaigns something more than a site for production and circulation of discourses critical of the state.

Foreign media’s description of Subay as the “Yemeni Banksy” is misleading because it stems from the ways that Western street art is often identified in terms of a process of artification, that is, the recognition of graffiti and street art as form of artistic expression with a consequent inclusion in museums, galleries, or markets (Heinich & Shapiro, 2012). This interpretation of Murad Subay’s practice might not coincide with local dynamics of “visibility” and access to social “recognition” (Honneth, 1995). Although the differences of perception are not at the center of this study, it is worth stressing that they highlight the ways in which what is observed internationally as urban and public art is locally used as a sensitizing device (Traïni, 2009). Connecting the study of emotions, collective action, and mobilization,6 French sociologist Christophe Traïni (2009) defines these types of devices as “all the material support, the placement of objects, and the staging techniques that the militants exploit, in order to arouse the kind of affective reactions which predispose those who experience them to join or support the cause being defended” (p. 15, Traïni, 2016). As opposed to studying sensitizing devices in a given mobilization, in the following pages, I explore street art as a device used to express issues that become considered as worthy of collectively being shared and denounced, and the potential capacity of mobilization that this use of painting on public spaces can have in the short or long term. Having participated in the contentious occupation of public space at Change Square in 2011, Murad Subay’s commitment to street politics and to the revolutionary public sphere deepened. My approach is to study his street art campaigns as devices that encouraged political action in the period following the ousting of power of former president Saleh.7

Although the study of the contentious movement initiated in 2011 is far beyond the scope of this article, the political and social learning that took place at the Square remains important to my analysis. The fact that people enhanced their understanding of direct political participation and political action from the street in rejection of institutional politics is certainly an element present in practices such those analyzed in this article. Experiences such as the artistic ones developed by Murad Subay linked the contentious street politics learned at Change Square to the transitional period that immediately followed as Saleh resigned in November 2011 and formally left power in February 2012, when former vice president of the country since 1994 and of Saleh’s party Abd Rabbo Mansour Hadi became president. But such artistic actions took place not only during this transitional period, but they also continued as the escalation of violence reached unprecedented levels since the end of 2014, when Huthi rebels launched a military offensive against Abd Rabbo Mansour Hadi’s government. As the military intervention led by Saudi Arabia against the Huthi in March 2015 marked the beginning of the war that is still ongoing in 2017, street art interventions continued to take place in the capital and its surroundings. As I will demonstrate in the following section, using street art techniques, this initiative organized around street art practices transformed walls, streets, and the city into a territory for collective and participatory experiments of an artistic and political nature.

From political uses of street art to aesthetically invested political devices

The myriad of ways in which people practiced participatory politics in the streets of Change Square were reflected in the transformations taking place in a variety of other fields. Among them, artistic practices were also combined with expressions of political claims. During 2011, the use of painting and photography reflected an interest mainly centered on the space of the Square, thus serving to support and reiterate slogans enduring the mobilization by symbolic means. In other words, these forms of visual expression (especially photography) were mainly used to record life inside the Square reflecting little or no interest in showing what was happening in the rest of the city.8

As the first months of the mobilizations passed, some photographers and bloggers turned their attention to the streets surrounding the Square, which was blanketed gradually by colorful graffiti and free writing used to support the mobilization. Similar to photography or painting, these techniques of street art also contributed to give an artistic expression to political claims. This practice was not unprecedented in Yemen. Before the revolutionary period of 2011, street art techniques had been used in Yemeni cities mainly to reflect religious messages through stencils displaying “God is the greatest” or “there is no God but God” or to reproduce political slogans and symbols of political parties. As is the case also in other countries, art was not the first intention of their anonymous performers (Figure 1).9

Figure 1. “Pray for/on the Prophet,” “God is the greatest,” “There is no God but God, and Mohammed is God’s messenger,” and the horses symbol of Ali Abdallah Saleh’s party, the General People’s Congress, photographed by the author in Sana’a 2009–2010.

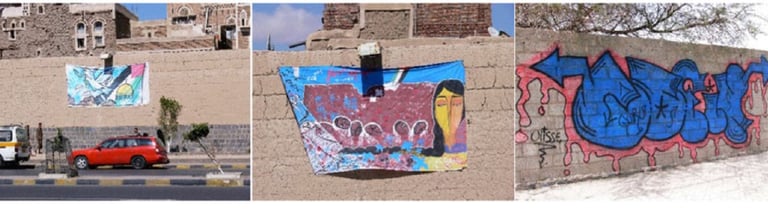

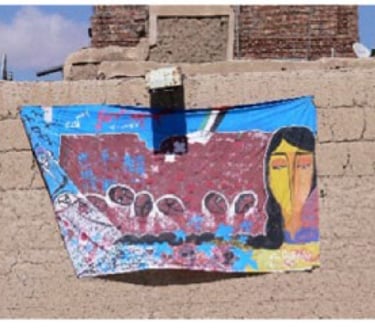

Two cases stand out in the use of techniques associated with street art prior to 2011 due to the fact that they involved painters. The first one took place in 2006, when a group of female painters from the coastal city of Hodeidah chose a wall to paint their first collective piece (Alviso-Marino, 2017). This group called “Halat Lawniyya” (“Colored haloes”), composed of five former students of fine arts from the University of Hodeidah, chose the celebration of Yemen’s unity on 22 May to unveil a painting collectively done on a wall of their city. The second example took place in 2009 in Sana’a, when several painters participated in making mural paintings that they hung on the walls of the old city, using public space to display solidarity with Palestine at a time when Israel renewed attacks on Gaza. In 2010 and 2011, “tags” or signatures aesthetically related to graffiti started to appear in certain walls of Sana’a (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Mural paintings hanging in the old city of Sana’a in solidarity with Palestine, 2009, and a tag photographed in 2011. Images by the author.

In 2011, these different techniques were being used in the walls nearby Change Square to visually reenact the slogans that were being chanted by the demonstrators. If the walls of cities such as Aden had already been used to make political claims through free writing prior to 2011,10 in Sana’a and around Change Square, these techniques became aesthetically more complex. In this vein, the word “irhal” (leave!), largely written on walls, asphalt, and street signs, started to appear written both in Arabic and in English using colorful calligraphy. Fists were reproduced against bright colors, people’s silhouettes marching in protest and holding the Yemeni flag were painted, and implied references to social media were displayed on the walls. In the context of a movement and a time perceived as revolutionary, issues of anonymity appeared less central to a practice otherwise characterized and built around the preservation of an anonymous identity by its European, North and South American practitioners.11 Under the circumstances of open critique and protest, some of the graffiti appeared deliberately signed and dated although most of it, together with the free writing on the walls, was typically anonymous. The street art that appeared in these walls was directly linked to the mobilization and portrayed its political goals through visual means (Figure 3).

Figure 3. From left to right: “Leave oh killer,” photographed by Abd al Rahman Taha, May 2011. “Leave,” “33 years are enough,” “Get out,” Revolutionaries and “Delete Ali?” courtesy of Jameel Subay, May 2011.

In 2012, a series of changes occurred in Yemen’s street art. Between March 2012 and 2017, street art campaigns were launched by a young painter in his twenties through Facebook. The city’s aesthetic was drastically transformed as kilometers of walls ended up being covered by painting and spray, in the capital Sana’a as well as in other major cities such as Taez and Aden. Most importantly, public space was again being used to express dissent and make social critiques, this time through painting in a collective manner. The practice of techniques related to street art was thus being transformed and singularly triggered by the campaigns launched by Murad Subay.

Color the walls of your street: local campaigns and international visibility

A student of English Literature at the University of Sana’a, Murad Subay was born in 1987 in Dhamar. Raised by his mother (his father is a blue-collar worker who emigrated to work in construction in Saudi Arabia), he grew up in his village of Dhamar, and later in Sana’a, and was greatly influenced by his older brothers. In a similar manner as they became interested, respectively, in poetry, writing, and photography, he turned toward the world of arts at the end of his adolescence. As they and his sisters actively participated in contentious politics, through their written or photographic work as well as through demonstrations and inclusion in activist networks related to the defense of human rights and freedom of expression, this environment contributed to Murad’s political socialization. Coming from this background and living not far from where the demonstrations against the regime took place at the beginning of 2011, he participated for the first time in a collective political action through the sit-in of Change Square in Sana’a. He was among the youth who started the sit-in in February 2011, and he quickly volunteered to monitor the entrances in order to avoid arms into the Square.

Subay had been interested in painting from a young age, but until 2012 had never exhibited his work, feeling that he was not ready yet to do so. Although he knows the artistic circles of the city, he does not participate in any of them.12 As a self-taught painter, he mainly practiced on canvases until he started to paint on walls in 2012. As Subay explained, he learned about the techniques of street art through the Internet and identified his projects with this form of expression as it provided him with a “quick and easy way to pass messages to Yemenis and to the world” (M. Subay, personal communication, 9 October 2012 and 24 December 2013). From March 2012 through early 2017, he has worked on five street art projects, which he describes in terms of campaigns.

The first campaign, named “Color the Walls of your Street” (lawun jidar shari‘ak) was launched in March 2012 as a call to color bullet-marked walls where violent clashes occurred in 2011 between the regime and demonstrators. When he started painting on the walls of the “Kentki roundabout,” at the crossroad of the streets Zubayri and Da’iri in Sana’a, he did so by reproducing his own paintings, previously confined to canvases. The walls then started to be covered by white hand-shapes painted over a black background or square-shaped faces put together as if they were a collection of puzzle pieces (Figure 4). They were all accompanied by two pieces of information present in pictorial art: the date and the full signature, easily legible, echoing the original canvases. Progressively, his paintings became art works of public access, also inspiring other participants who followed his initiative.

Figure 4. “Color the Walls of Your Street,” courtesy of Murad Subay.

The campaign was a success in which not only painters and those responding to the Facebook announcement participated but also passersby joined them as they painted. Print and TV media were also attracted by what quickly became a collective artistic action, covering the transformation of walls as they were being sprayed and hand painted. Abstract images of giant faces, lists with Yemeni names written in ancient south Arabian alphabet, and colorful compositions appeared next to paintings that also carried social comments. For instance, a child burning a gun, a simple drawing where a message in English declared “I don’t have a job” (Figure 4) or the word “jobless” written in Arabic highlighted the political impact that artistic expression in public places could have as devices to render people aware of social problems. This use would later be deepened in the subsequent campaigns undertaken by Subay.

For “Color the Walls of your Street,” Subay conceived a campaign that was in his understanding a way to distance himself from politics, which he perceived as “disgusting” (qadhara). He wanted to beautify his city at a time when power struggles disgusted him the most and he chose to do so through painting on walls that could not be politically neutral. As a reminder of the deaths that had occurred against pacifist demonstrators,13 bullet-marked walls were chosen for this campaign in order to embellish the streets while remembering history still in the making. This project effectively distanced Subay from institutional and partisan politics but rooted his practice in the street as a site for enacting social and political critique and as a “place of memory of the revolt.”14 Furthermore, he carried out a collective project massively joined as kilometers of walls testified, using public space without any authorization.

These elements, as well as the political character of the space chosen, allow us to draw parallels between his artistic practice and his learning of street politics. A year before this first campaign, he participated in a popular mobilization that started using public space also in an unauthorized manner. In 2012, he transformed the political and social capital acquired under the tents of Change Square into an artistic endeavor, inscribing his practice in a “politics from below”15 approach that translated into an “arts from below” campaign. This first campaign also provoked changes in the way painting could be practiced, exhibited, and performed. Contrary to being secluded in a closed space or individually performed, paintings were all over the streets fully signed and dated.

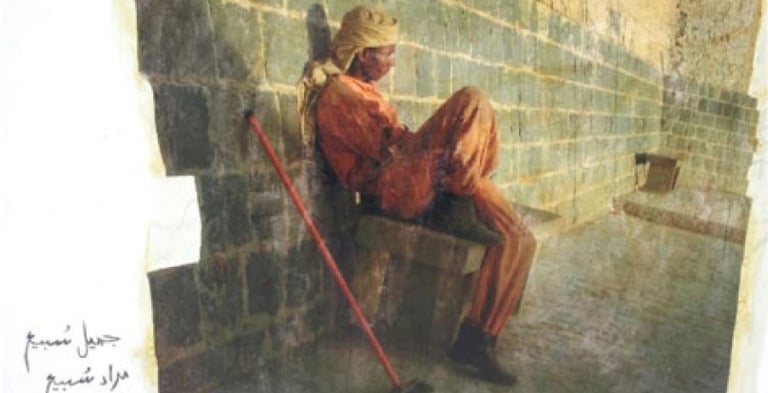

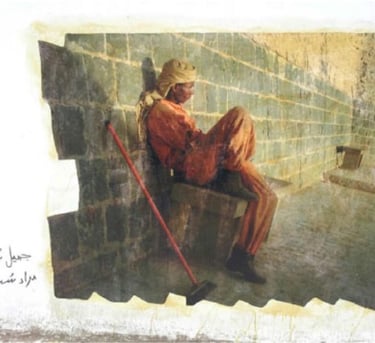

The brushes and the sprays used for these paintings were temporarily substituted for wheat paste during the summer of 2012. In this instance, Murad Subay carried out a different project where he pasted photographs taken by his brother Jameel Subay. This time he did not post an announcement on Facebook or define his intervention as a “campaign,” but he chose images and walls that were all but politically neutral. The images he enlarged and borrowed from his photographer brother were used to show solidarity and visually enact social commentary. In fact, Jameel Subay had published or exhibited some of these images in order to question poverty, exclusion and war, and the ways in which attention can be deviated from these issues. By pasting images of such content on the walls of the city, the issues they pointed out acquired a greater visibility in a context that made them all the more pertinent. Learning from the Internet the characteristics of the technique, Murad pasted three photographs: one portraying a street cleaner mostly known as akhdam,16 which served to show solidarity with them at a moment when they undertook a strike (Figure 5). Another representing a man carrying aloe leaves was pasted on the Police Academy walls where a bomb attack claimed by al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula had taken place in July, killing cadets who were leaving the academy at the moment of the explosion. Next to the photograph, he wrote “aloe to their souls,” with the intent to offer “a present to the souls of the dead as one offers flowers in a funeral” (M. Subay, personal communication, 7 August 2012). The third image exhibited a person sitting on the floor, the back facing the viewer, which in Murad’s eyes served to point out when Yemenis “give their back and ignore what is happening” (M. Subay, personal communication, 7 August 2012). These three images were signed and dated under Murad and Jameel Subay’s names and did not capture any media attention (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Courtesy of Jameel Subay.

Following this project, Subay carried out a new campaign that started in September 2012 and continued through 2013. Named “The Walls Remember Their Faces” (al-judran tatadhakar wajuhahum), it was used to point out a political issue: the forced disappearance of activists, journalists, and citizens in general from the 1970s until today.17 The government, both in former North (then presided over by Saleh) and South Yemen, but also Saleh’s most recent regime, are suspected of being responsible for the disappearance of an unknown number of citizens. As he did for his first campaign, Murad announced it on Facebook and recurred to the Internet to learn about the use of stencils. Thus, he conceived of stencils that included a portrait of the person who disappeared, his name, a line saying “enforced disappearance,” and the date it happened, all both in Arabic and English (Figure 6). The first stencils were sprayed in the early morning for fear of repressive reactions, but as the campaign grew in numbers of participants and media coverage Murad changed tactics. He then chose to ask for permission to the authorities in order to stencil walls placed along main roads. In some instances, the stencils were erased or painting washed, only to be quickly restored by participants who joined Subay in this campaign. The fear was justified in a context where the military, suspected of having participated to the disappearances, was largely present in the streets of Sana’a. As Murad Subay stated, “it is a sensitive issue for them, it makes them fearful. The eyes of those who disappeared watch the killers, the officials with blood-soaked hands, right in front of their houses” (Al-Shamahi, 2013). Subay was authorized to spray his stencils and was joined by a large crowd of participants. His campaign not only served to point out an issue of social concern but also triggered a larger process of collective memory recovery. Participants in the campaign stenciled the images, but they also provided pieces of information about the disappeared citizens or photographs to produce new stencils that ended up reaching the hundreds. They commented and exchanged information about their own disappeared family members, participated in arguments with the military present in the streets, and became agents in the process of finding more information about the whereabouts of their family members or acquaintances.

Figure 6. Courtesy of Murad Subay.

This campaign was clearly a contentious one, making claims and demands to the authorities in power and having several consequences for people aside from the participants themselves. The creation of a special committee to investigate and file cases of enforced disappearance, the discussion over the elaboration of a transitional justice law, and the attention of the Human Rights Minister to promote debate at the institutional level are some of the consequences that resulted from the stencil campaign. Although this issue had been raised previously in 2007 (Farhat, 2013), it was the stencil campaign that produced the most important impact via public participation and the recovery of collective memory, resulting in inclusion of the issue in the political agenda and contributing to finding alive some of the forcibly disappeared.18 The result was a campaign that, initiated by a painter, gave rise to an unintended collective action with consequences never initially imagined.

The large participation that accompanied Murad Subay’s campaigns as well as the media coverage he benefited from encouraged him to transform his practice and even teach his technique in a more institutionalized way. In May 2013, he conducted a workshop at the French Institute in Sana’a where he taught students how to draw, cut, and spray stencils that reproduced the faces of poets, writers, thinkers, or, more generally, local and international prominent figures, whose portraits were then spray painted on the walls of the French Institute. Only temporarily, he concealed his practice inside an institution while simultaneously continuing to develop new campaigns.

Among the changes that have taken place from one campaign to the next, the most important has been the clearer definition his street art projects have acquired as political sensitizing devices. From the first campaign to the most recent one, the political scope of his artistic practice has been consolidated. For instance, the campaign titled “12 Hours” (12 sâ‘a) was designed by Subay to “pass messages of political content,” hoping that his work would have an impact locally and also internationally. He chose for this project the busy commercial streets of Zubayri and Haddah, filling the walls with images spray and brush painted, accompanied by a text written in Arabic and in English. Other painters joined him, both male and female, reaching a total of six. This campaign unfolded as a series in which each intervention in the public space corresponded to one precise hour that was inscribed in a stencil showing the time. For a year, between 2013 and 2014, the interventions or “Hours” painted on the walls directed attention toward specific subjects such as arms proliferation, sectarianism, kidnapping of foreigners, trampling of the nation, drone attacks, poverty, civil war, corruption, or social marginalization, among others (Figure 7). For instance, the “eight-hour,” which Murad planned for 6 March 2014, was dedicated in his own words “to paint the faces of the victims who were killed at Aurdhy Hospital after a terrorist attack claimed by Al Qaeda Arabian Peninsula, or maybe I should say after the terrorist massacre” (M. Subay, personal communication, 5 March 2013) (Figure 7). His hope was to paint on the walls of the Aurdhy Hospital itself, and since he considered this a politically sensitive action, he requested authorization that was denied by the Ministry of Defense, deciding then to find other suitable walls. The “12 Hours” campaign ended on the 1 July 2014, with a stencil that reproduced Subay and another painter, a list of all the accomplished hours, and Murad writing “we won’t be silenced.” Following this campaign, he traveled to Italy in November 2014 to receive the Art for Peace award from the Veronesi Foundation. He then returned to Yemen and used the money he received to work on another unprecedented project he formulated as a sculpture campaign.

Figure 7. Courtesy of Murad Subay.

In January 2015, a month before President Abd-Rabbu Mansour Hadi escaped house arrest and Huthi rebels took over power, Subay together with a group of artists and activists put the first (and only) sculpture of his fourth campaign in the middle of a commercial street of Sana’a. The sculpture evoked an ancient symbol, “Elmuqah,” related to national unity. Subay wanted to stress Yemenis’ expertise at state-making with a symbol commemorating that 3000 years ago “the tribes in Yemen wanted to make a state and they united their gods, the star, the moon and the sun” in one god that is “Elmuqah” (M. Subay, personal communication, 26 January 2015). At the beginning of the campaign, Subay feared that the Huthis would prevent him from continuing with the project, but he still planned to put up more sculptures on the streets. Ultimately, however, the deterioration of the political situation interrupted this project and the war, and the lack of electricity made it impossible for him to continue (M. Subay, personal communication, 2015).

During the period from the end of “12 Hours” campaign in July 2014 through the beginning early 2015, Subay’s artistic trajectory was marked by a number of opportunities to exhibit his work outside of Yemen. For instance, in September 2014, he exhibited street art works in an art center in the United States and abstract paintings in a gallery in Kuwait. In the United States, this opportunity took place through his political work: the stencils and paintings he made for “12 Hours” were reproduced within the walls of the Helen Day Art Center in Vermont. The title of the exhibition, “Unrest: Art, Activism & Revolution,” aimed to reflect in the words of the curator “the impact artists have on the political and social reform of countries like Egypt, Yemen, Israel, Palestine, Iran and the United States” (Moore, 2014). According to the description of the exhibition on the art center’s website, this exhibition “looks at artists as activists, revolutionaries and visionaries” (Moore, 2014). This collective exhibition, featuring internationally renowned artists such as Iranian Shirin Neshat and Egyptian artist Lara Baladi, gave Murad’s work a visibility that values the political content of art. Such was not the case with the work he exhibited in Kuwait at the Contemporary Art Platform (CAP). In Kuwait, the exhibition featured his most abstract work, devoid of any political content, with other similar works made by other artists whose background or country of origin could not be established (M. Subay, 2014).

The first of these exhibitions can be identified with a dynamic of artification and thus interpreted as an opportunity to include street art as an artistic object within spaces that recognize it as such. These experiences that bring international visibility seem to be opportunities seized by Subay when they arise but do not guide his practice, which is centered in the street. The fact that public space is privileged within his trajectory reflects a deliberate choice to inscribe his work in mainly noncommercial places with the aim of reaching a local public and creating awareness, engagement, and participation around political issues through artistic interventions. These opportunities to access visibility (through exhibiting outside of Yemen) and to reach a certain level of recognition (winning prizes) also suggest that the politicization of art when it is associated with the countries which, following the 2011 revolutionary period, saw their populations mobilize for regime change in authoritarian contexts, is a viable way to gain access to visibility; valorization; and, potentially, social, economic, and artistic recognition.

Such visibility was noticeable during Subay’s latest campaign, “Ruins,” which began in May 2015 and continued until 2017, in the middle of which he was awarded the “2016 Freedom of Expression Arts Award” by the Index on Censorship organization in the United Kingdom. This campaign explicitly exposes war crimes and focuses on giving visibility to the lives lost due to the bombings of the Saudi-led coalition. In Sana’a, as in other parts of the country, the bombings have left whole districts in ruins. Subay painted 27 flowers on a wall next to the ruins that remain after a missile killed 27 people, including 15 children, in Bani Hawat, close to Sana’a (M. Subay, personal communication, 11 June 2015) (Figure 8). Two days later, one of the biggest explosions caused by air attacks took place in the capital. Murad and his friends went to the scene and made paintings on ruined walls where dozens of people were killed near the mountain Faj Attan.

Figure 8. “Ruins” campaign.

Courtesy of Murad Subay, June 2015, Bani Hawat.

Throughout all five of Subay’s campaigns, certain elements converge and others fluctuate. Common to all is the use of public space and of collective initiatives aimed not only at painters but to encourage public and unanticipated participation. In all cases Murad paid for materials from his own pocket. When approached by family and friends on the financial issue, he has only accepted help in the form of painting supplies and, of course, participation. He contends that the success of these campaigns resides in economic independence. Equally self-financed are the campaign participants, who often offer materials that are shared by Subay and the rest of the painters. Furthermore, the choice of the walls and the streets is also a central common feature of Subay’s interventions, highlighting the stakes of territorial appropriation. The streets are chosen in order to grant greater visibility or to provide the artistic intervention with a peculiar meaning. A wall can thus be selected due to the symbolic meaning of the street where it is located, as emblematic spots associated with the mobilizations of 2011 or as destroyed walls that point out at the violence of an ongoing war. The issue of space also informs an element that appears to be fluctuating in Murad’s projects: the question of painting in authorized or unauthorized places. In this vein, the first and the last campaigns did not imply a need for permission and largely took place on unauthorized walls. Since the second campaign, Murad mixed the use of unauthorized walls with permission from the authorities. This strategy was present in the realization of one particular intervention within the “12 Hours” campaign, which was planned to take place on walls that were later denied by the government. The demand of permission seems to articulate around the perception Murad has of the risks his actions might take in terms of the political claims he makes. Finally, the issue of the effects achieved by these campaigns appears as always unexpected. The case of the stencils portraying disappeared citizens has been so far the only one that generated a collective action with consequences at the institutional level, leaving the possibility open for future interventions to generate such changes or to be conceived with this possibility in mind.

© 2025. All rights reserved.